In today’s “Ingredient Spotlight” we’re looking at the slightly mysterious world of yeast. Yeast has been used to ferment things for many centuries but it’s only relatively recently that we’ve actually started to understand how it works.

For thousands of years, humans have used yeast in food and beverage preparation. Our ancestors understood that something special happened when this strange organism interacted with other ingredients to create alcohol or other funky flavours in our food and drink.

However it was only in the last few hundred years, through the pioneering work of scientists such as Anton van Leeuwenhoek and Louis Pasteur that we began to understand that yeast is a living organism and not something “magic”. The work of these and other researchers brought the study of yeast into the world of science.

What exactly is yeast?

Yeast is a single celled organism that consumes sugars and creates carbon dioxide and alcohol as a by-product. It is technically part of the fungi family but behaves quite differently to most other fungi. It has been used in baking and brewing for at least 4000 years. Yeast is probably the oldest organism that has been domesticated by humans and has truly shaped the way that humanity prepares and consumes food and drink. We as humans utilise thousands of different yeasts for all manner of dishes and drinks – there are literally countless yeast strains around the world.

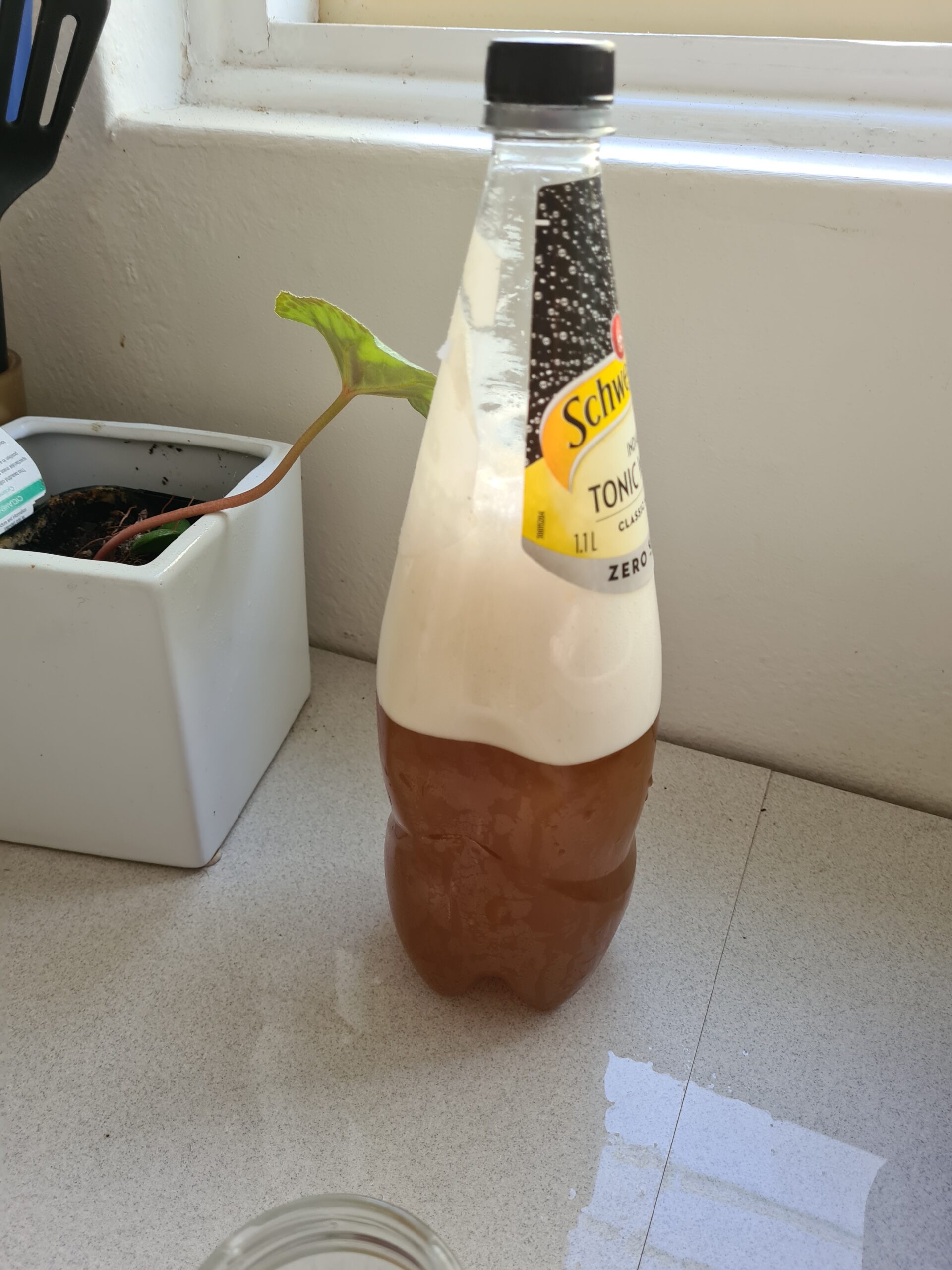

The word yeast comes from the Old English word “gyst” or “gist” which means to foam, bubble or boil. If you’ve ever seen yeast at work, you’ll understand why they chose this descriptive word.

Yeast plays a crucial role in the brewing of beer. Yeast is responsible for the fermentation process, which is what turns the sugars in the malted barley into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Without yeast, beer would not be possible.

During the brewing process, yeast is added to the wort, which is a mixture of water, hops and malted barley that has been boiled and then cooled. The yeast then begins to consume the sugars in the wort and produce alcohol and carbon dioxide as byproducts. This process takes place in a fermenting tank or vessel and can take anywhere between a few days or even months (depending on the style of beverage and strain of yeast). Once the yeast has consumed all available sugar, the beer is more or less ready for consumption (after some carbonation and conditioning).

There is a saying amongst brewers: we prepare the wort the yeast does the brewing. Yeast is a crucial link between the sugary malted barley and the delicious beer that we pour into a glass.

CHECK OUT: The Best Foods To Pair With Cold Beer

Types of yeast

There is an incredible spectrum of yeast available for brewing beer. Aside from the hundreds of commercial strains available, there are endless wild and mutated strains that can help brewers to create the perfect brew. Beer yeast fall into roughly three categories: ale yeast, lager yeast and wild or specialty yeasts. All these yeasts behave differently and offer different flavours.

Ale yeast (scientific name Saccharomyces cerevisiae) has been used for many years to, unsurprisingly, make ales. These yeasts will generally impart a more fruity or nutty aroma which is typical of ale. They like a temperature of around 20C and are “top fermenting”. Top fermenting refers to where the yeast activity takes place – if you pop open an active fermenting vessel, you’ll see a foamy, bubbling layer on top of the wort as it ferments. This is known as a “Krausen” and is typical of ales. It should be said that there are many, many strains of ale yeast that are specifically bred for certain conditions and recipes. For example the hardy Safale US-05 will achieve a neutral flavour and the rustic saison yeasts will impart a distinct funk in the brew and is more tolerant of higher temperatures.

The other yeast that is popular in brewing is lager yeast (scientific name Saccharomyces pastorianus) this yeast was isolated by Emil Hansen in a lab at the Carlsberg brewery in the late 18th century. This discovery was so significant that it is said that after the yeast was isolated, armed guards were stationed at the lab to protect this important proprietary discovery. Unlike ale yeast, lager yeast ferments from the bottom of the fermenting vessel and prefers cooler temperatures. Lager yeast will leave a crisp, cleaner taste that is characteristic of the lager styles that we enjoy today.

There is also a third category of yeast that includes an almost infinite amount of other strains: wild and specialty yeasts. These are often collected from nature or allowed to form on an open fermenter naturally. They may also accumulate on brewing gear (especially wooden casks or barrels) These yeasts are incredibly diverse and often certain beers can only be made in specific brew houses because the yeast and other good microbes are impossible to replicate under other conditions.

Buying and storing yeast

Yeast requires very specific conditions to thrive. This is true not only when we add it to our wort (called “pitching”) but also when we buy and store our yeast. Too much time in adverse conditions may reduce the viability of our yeast or even kill it all together.

It is important that yeast is purchased from reputable suppliers and resellers. If the yeast has become too hot in transit or sat in a warehouse for months, there could be issues when it comes time to brew. A really good retailer such as a trusted home brew store will have confidence in the handling of their products from lab to shop. Typically yeast should be refrigerated at the point of sale, however this is not always strictly necessary – especially with some of the more hardy dry yeasts.

Yeast for home brewing is typically bought in two forms: dry and liquid. Liquid yeast comes in a vial and while dry yeast comes in packets. The medium you choose will depend on what strain you want, how you like to pitch and personal preference. I personally feel that dry yeast does just as good a job as its expensive liquid cousin however there are certain specialty strains that simply cannot be obtained in dry form.

Once you have your yeast, it is generally best to keep it refrigerated until it’s time to use it. Pull it out of the fridge an hour or so before it’s time to pitch to allow it to return to ambient or room temperature. Your packet of yeast will likely have instructions relating to storage and pitching temperatures – it’s always best to follow these instructions where available.

I would also suggest having a couple spare packets of your most used strains in storage ready to go. Despite proper handling and storage practices, you will occasionally come across “dud” packets that don’t have enough viable cells to get fermentation started. Not having a spare ready to go can really create issues on brew day. If you are worried about the viability of your yeast, you can also make a starter for your beer by adding your yeast to a mixture of Dry Malt Extract (DME), wort or other sugars. This will create a smaller fermentation before the mix is added to the main brew. The process and calculations for creating a yeast starter is too much to go into here but there is plenty of great info online!

Yeast is an essential part of the beer making process. Although the science behind this mysterious microorganism was not understood for thousands of years, it has been an integral part of the human experience for many years